The following entry is the translation of the appendix A of my thesis, initially written in french (French readers are thus invited to read it directly there). Surprisingly, one year after writing it, I still more or less agree with its content and thought it might be of interest to a broader audience, especially students and young physicists. I do not claim that it contains anything particularly new on foundations and is just aimed at taming the confusion that dominates the field, especially for beginners.

“Bohr brainwashed a whole generation of physicists

into thinking that the job was done 50 years ago. ”

Murray Gell-Mann

The existence of the problem

The foundations of quantum theory have an interest only if there is a problem to solve, something not every physicist is ready to concede (see e.g. Fuchs & Peres). Hence before doing the apology of a rigorous exploration of foundations, we should first convince ourselves of the seriousness of the preexisting problem.

The fundamental problem of the standard formalism of quantum theory is that is does not allow to derive the existence of a tangible and objective macroscopic world. A corollary, which is often the focal point of the debates, is the measurement problem, that is the impossibility to reduce the measurement postulate to unambiguous physical phenomena.

To my knowledge, there are two broad possible negations of the very existence of this problem:

-

the problem has already been solved by the “modern” theory of decoherence which explains in a satisfactory way the emergence of facts,

-

the problem comes from an outdated philosophical prejudice. There is no reality or, rather, talking about it amounts to leave the realm of science to compromise oneself with metaphysics.

In the first case, one admits the problem is real or at least has been, but one claims that it is solved by the theory of decoherence, which, because it can reasonably be considered to be part of the orthodox formalism, does not belittle its supremacy. In the second case, one criticizes the very legitimacy of the question using a lazy positivistic argument. It seems to me that those who remain unmoved by foundations are separated roughly evenly between these two categories or oscillate between the two lines of defense depending on the situation. It is useful to explain why those two arguments are inadequate; more precisely demonstrably false for the first and philosophically dubious for the second.

Decoherence

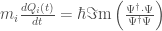

The objective of the theory of decoherence is to explain how the coupling of a system of density matrix  with an external environment with a few reasonable properties yields the quick decrease of the non-diagonal coefficients of

with an external environment with a few reasonable properties yields the quick decrease of the non-diagonal coefficients of  in a certain basis. The theory of decoherence allows to understand both the speed at which coherences vanish and the choice of the basis in which

in a certain basis. The theory of decoherence allows to understand both the speed at which coherences vanish and the choice of the basis in which  is diagonalized. We should immediately note that this program has been a success (see e.g. [Zurek1981]). Zurek and his collaborators have shown, through difficult and undoubtedly elegant derivations, that the phenomenon is robust and universal.

is diagonalized. We should immediately note that this program has been a success (see e.g. [Zurek1981]). Zurek and his collaborators have shown, through difficult and undoubtedly elegant derivations, that the phenomenon is robust and universal.

Nonetheless, — and the profusion of new concepts such as einselection (for environment induced superselection, see [Zurek2000] or [Zurek2003] ) or the slightly pedantic Quantum Darwinism [Zurek2009] changes nothing — decoherence only explains the diagonalization of  in a certain basis and says nothing about collapse. Even if the main contributors to the theory rarely explicitly claim to solve the measurement problem, they unfortunately maintain the ambiguity, especially in articles aimed at non specialists [Zurek2014] .

in a certain basis and says nothing about collapse. Even if the main contributors to the theory rarely explicitly claim to solve the measurement problem, they unfortunately maintain the ambiguity, especially in articles aimed at non specialists [Zurek2014] .

Let us recall briefly why diagonalizing the density matrix is not enough. The mathematical part of most articles on decoherence consists in showing that in some more or less general situation one has:

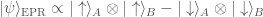

It is known how to determine the basis of diagonalization and the latter agrees with what one would expect the pointer basis of the corresponding realized measurement to be. It is an undoubted success of the method: decoherence allows to explain what observable a given measurement apparatus actually measures, provided one admits that the latter collapses. At this stage, there is a philosophical leap that one should not do but that is often irresistible: identify the obtained diagonal density matrix, which corresponds to an improper mixture, with the density matrix coding for a true statistical (or proper) mixture. This confusion is what is sometimes called a category mistake in philosophy: two fundamentally different objects are abusively identified because their representation is identical. It is an error one would never do in any other situation. Consider for example an EPR state shared between Alice (A) on the left and Bob (B) on the right:

The reduced density matrix, from the point of view of Alice, can be written in a very simple way in the  basis:

basis:

.

.

Does one conclude, in this situation, that the very existence of a part of the quantum state on Bob’s side makes classical properties “emerge” on Alice’s? Even assuming Bob’s state is forever inaccessible, the answer is clearly no. The object  cannot be assumed to be a statistical mixture without violating Bell’s inequality. In that case, identifying two physical situations because their mathematical representation is the same yields an obvious error. It is however the exact same substitution one does when trying to deduce macro-objectification from decoherence. The magical trick is usually done at the very end of the article, in a few sibylline sentences after long yet reasonable computations and thus often remains hard to spot.

cannot be assumed to be a statistical mixture without violating Bell’s inequality. In that case, identifying two physical situations because their mathematical representation is the same yields an obvious error. It is however the exact same substitution one does when trying to deduce macro-objectification from decoherence. The magical trick is usually done at the very end of the article, in a few sibylline sentences after long yet reasonable computations and thus often remains hard to spot.

We should note that this confusion around the claimed “foundational” implications of decoherence does not only have philosophical or metaphysical consequences and has given a fair amount of problematic extrapolations in cosmology and quantum gravity (see the references in [Okon&Sudardky] for a discussion). The situation nonetheless seems to slowly improve as the recent change of mind of Steven Weinberg on this matter shows; proving as an aside that even in this sensitive topic, smart people do change their mind.

Observables and perceptions as the only reality

Another option to refuse to seriously consider the measurement problem is to abide by an extreme form of positivism that can be caricatured in the following way. The objective of science being in fine to produce a set of falsifiable predictions, physical theories should only be formulated in terms of what is observable, talk only about results. Digging below the result, “microfounding” it, reducing it to a phenomenon would have no meaning because the result itself is the only thing that is objective. There is thus no difficulty with the axiomatisation of quantum theory that provides an algorithm that one knows how to implement in a non ambiguous way, at least for all practical purposes.

However, it is important to understand that such a vision of science is extremely restrictive and in no way implied, e.g. by Popperian epistemology. The fact that predictions are the ultimate product allowing to test or falsify a theory does not mean the latter cannot use a certain picture of reality as an intermediary, letting results emerge. Results and observables need not be primitive notions to be taken seriously. If this change of perspective were necessary, made totally unavoidable by experimental results, then one might understand or even justify such an instrumentalist attitude. However, as we will see, this is not the case. A point of view often belittled as classical is totally acceptable. Assuming that there is a world out there that exists in an objective way, measurements being only specific configurations of this world, is indeed in no way incompatible with the predictions of quantum theory.

A modern and trendy variant of the previous argument is to say that the only real thing is information (or, sometimes, quantum information, whatever that is supposed to mean), that the quantum algorithm is simply an extended probability theory that rules its exchange, reality being again in information itself. One may perfectly find that this point of view has merits as a heuristic guide, especially in the context of repeated measurements (and perhaps quantum thermodynamics). Yet, it seems impossible to take it seriously as information cannot be a primitive notion. Indeed, pure information does not exist and is a meaningless concept: one always has information about something. It is this “something” that one should define to make the approach rigorous; why not just do it?

A spectrum of solutions

Theories with a primitive ontology

Let us start by warning the reader that this section does not aim for comprehensiveness (for which one should rather check [Laloë]) and many approaches are voluntarily ignored. The objective is simply to present one possible way to construct theories that reproduce the results of the orthodox formalism without being plagued by its ambiguities.

It is possible that one finds very subtle and counter intuitive ways to construct reasonable physical theories in the future. In the meantime, one possible way, almost naive, is that of theories with a primitive ontology (see Allori et al.). It is only the modernized vocabulary of Bell’s proposal of local beables. Behind this uselessly pretentious word, which makes physicists draw their anti-philosophy revolver, lies an extremely simple notion. The ontology is simply what there is, physicists would say “reality“, Bell beables. The word “primitive” means that this ontology is the basis giving its reality to the rest and that does not require to be further explained in terms of more “primitive” concepts (such as the atoms of Democritus). It obviously does not mean that what one considers to be primitive cannot change as time goes by and our understanding of the world improves. It only means that what a given physical theory considers to be primitive should be precisely stated. One usually adds the constraint that this primitive ontology should be local, that is a function of space time (and not e.g. of configuration or phase space). A priori, nothing makes this constraint absolutely necessary, it simply allows to understand easily how macroscopic objects, that naturally live in space-time, emerge from the configuration of the primitive ontology. If doing this simplification is possible, i.e. always allows to construct consistent theories, then it would be stupid to not use it. We should note that there exists a wide variety of primitive ontologies that are a priori acceptable, that is, that allow to model the world: particles obviously, but also fields, why not strings, and more recently flashes.

Once the primitive ontology defined, the postulates of a physical theory should only prescribe its dynamics. The rest, observations, measurement results, all macroscopic behaviors, should be logically derivable as theorems. This is not revolutionary: classical mechanics –in which the ontology is simply the particles– fits perfectly well in this definition and no one would dare contest its scientific character. This approach, erstwhile awkwardly heterodox, seems to now be used by a larger and larger fractions of the physicists and philosophers interested in foundations because it makes discussions precise, essentially mathematical, and takes the debate away from philosophy. A theory based upon a primitive ontology is non-ambiguous and thus easy to discuss. No question is in principle forbidden as in the standard formalism; the theory somehow takes more risks than a pure “prediction” algorithm but is in return immediately intelligible.

We can now present very briefly (that is without proving that they work) 3 examples of theories with a primitive ontology that are compatible (up to  ) with the predictions of the standard formalism of non-relativistic quantum mechanics.

) with the predictions of the standard formalism of non-relativistic quantum mechanics.

The example of a particle ontology

The de Broglie-Bohm (dBB) theory, or pilot wave theory, has a very simple ontology: a given number of particules without properties or qualities move in space. Writing  the trajectory of the particle

the trajectory of the particle  on has the following purely deterministic equation:

on has the following purely deterministic equation:

.

.

The wave function  (which can be scalar, spinor or vector valued) evolves according to the “standard” unitary evolution (e.g. Schrödinger, Pauli-Dirac,…) and can be considered to have a nomological (law-like) rather than ontological (real) status. That is,

(which can be scalar, spinor or vector valued) evolves according to the “standard” unitary evolution (e.g. Schrödinger, Pauli-Dirac,…) and can be considered to have a nomological (law-like) rather than ontological (real) status. That is,  guides particles as a law and possesses a status similar to that of the Hamiltonian in classical mechanics (which prescribes the trajectories without being determined by them). It has been shown, and it is the product of a long work of physicists and philosopher because the result is not trivial, that this theory is empirically equivalent to the quantum algorithm so long as the predictions of the latter are not ambiguous (see e.g. [Berndl1995], [Dürr2009] or [Bricmont2016]). Hence, there exists a precisely defined theory, in which position and velocity are always well defined, in which the observer is a physical system like any other, that is fully deterministic and in which all the quantum weirdness can be reduced to a purely mechanical and causal (thus non-romantic) explanation.

guides particles as a law and possesses a status similar to that of the Hamiltonian in classical mechanics (which prescribes the trajectories without being determined by them). It has been shown, and it is the product of a long work of physicists and philosopher because the result is not trivial, that this theory is empirically equivalent to the quantum algorithm so long as the predictions of the latter are not ambiguous (see e.g. [Berndl1995], [Dürr2009] or [Bricmont2016]). Hence, there exists a precisely defined theory, in which position and velocity are always well defined, in which the observer is a physical system like any other, that is fully deterministic and in which all the quantum weirdness can be reduced to a purely mechanical and causal (thus non-romantic) explanation.

The dBB theory should not be seen as an ultimate approach to adopt or fight, but rather as a particularly clear and simple prototype of what a theory with a primitive ontology may look like. It is however not the only one and objective collapse theories can also be put in such a form. In that latter case one can have either a primitive ontology of fields or of flashes (one may also copy the dBB construction and put particles but we shall not discuss this option here).

Two ontologies for collapse models

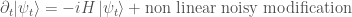

Before discussing the ontology of collapse models, one should perhaps say briefly what they consist in (see e.g. the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). The idea of collapse models is to slightly modify the standard linear evolution for quantum states:

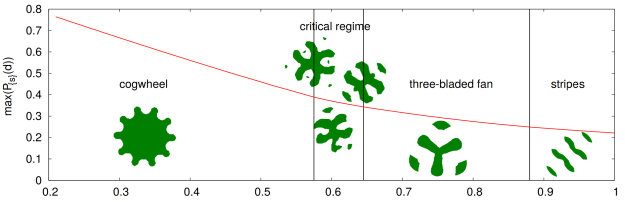

With this modification, the Schrödinger equation slightly violates the superposition principle. The modification can be chosen tiny enough that the standard quantum mechanical predictions hold for atoms and molecules but that macroscopic stuff is sharply collapsed in space. A typical example of such a modification is the GRW (from Ghirardi Rimini and Weber) model in which the wave function has a tiny objective probability to collapse into some sharper function:

The rate is small enough that atoms never encounter such collapses but that macroscopic bodies are constantly kicked towards well localized configurations in space. This, however, is not enough to solve all the problems with quantum theory. After all, the only object we still have is a wave function in configuration space, a very non-local object, hence definitely not a primitive ontology. A possibility to project down the wave function to a primitive ontology is simply to consider the mass density field:

,

,

where  is the mass density operator. This gives a continuous matter field living in space that we one can consider to be what is real in the theory. One then realizes that it is possible to account for all experimental situations (i.e. even spin measurements) in terms of fluctuations of this field. The wave function is then only a convenient computational tool to write the dynamics of the primitive ontology in a compact way. Of course, there are clearly many other possibilities but taking the mass density allows to readily understand the localization of macroscopic objects.

is the mass density operator. This gives a continuous matter field living in space that we one can consider to be what is real in the theory. One then realizes that it is possible to account for all experimental situations (i.e. even spin measurements) in terms of fluctuations of this field. The wave function is then only a convenient computational tool to write the dynamics of the primitive ontology in a compact way. Of course, there are clearly many other possibilities but taking the mass density allows to readily understand the localization of macroscopic objects.

Another option is to take the flashes, that is the centers of the collapsed wave functions after a collapse event, as the primitive ontology. One obtains a collection of space-time events, localized in space and in time, thus providing a very shallow reality. However, it is also possible to convince oneself that the world (with tangible tables and chairs) emerges at the macroscopic scale from this ontology in the same way as one sees the landscape only after zooming out from a pointillist painting.

The difference between these two collapse approaches and the dBB theory presented previously is the existence of some fundamental randomness in Nature: the two ontologies of collapse models contain a stochastic component, in the classic sense. On top of this, collapse models add some instrinsic decoherence which makes them slightly different from orthodox quantum mechanics (instantiated in the Standard Model) with respect to experimental predictions. These models can obviously be criticized for being ad-hoc and excessively fine tuned but one cannot deny that they are defined in a precise way without any reference to an observer.

One could worry, and actually one often worries, that there exists many possible primitive ontologies providing theories with the same empirical content. Does not it mean that ontologies are meaningless? Of course not, whatever the theory (not necessarily related to quantum mechanics) there will always exist infinitely many possible realities to explain a given set of results. The particle ontology of classical mechanics is empirically indistinguishable from an ontology of tiny angels, constantly breaking down and moving pieces cut from a continuous matter, miraculously reproducing the results of Newton’s laws. Does it imply that the ontology of material points needs to be abandoned in classical mechanics? That talking about atoms is bound to be meaningless? Of course not, choosing between different primitive ontologies can be made with the help of Occam’s razor that cuts through the invisible angels. One should not misinterpret Russell’s teapot argument: the existence of a teapot orbiting Saturne is not falsifiable but it does not mean that every ontology that does not directly manifest itself to our senses should be dismissed. We have no reason to believe in Russell’s teapot, we have some to believe in reality.

A few benefits of a demystified theory

Even if the reader is convinced that the previous program solves an actual physical problem, she may still question the practical use of the proposed solution. Has the orthodox approach not enabled tremendous technical progress? Why would the “shut up and calculate!” of Mermin be less legitimate today if one only care about what is true for all practical purposes? The objectif is now to show that from a purely opportunistic and pragmatic point of view, it is extremely profitable to have clear ideas about the foundations of quantum theory.

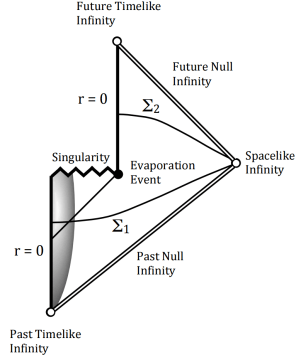

Having a class of precise theories reproducing the predictions of the orthodox quantum formalism provides a better basis (or at least a different basis) to generalize the theory, say to gravity. In this example, one can think of coupling the primitive ontology of a collapse model to space time to unify gravity and quantum mechanics with a peaceful coexistence of quantum and classical sectors, thus providing another indication that gravity need not necessarily be quantized. This idea has motivated a recent attempt by Lajos Diosi and I in the Newtonian regime. If one insists on quantizing gravity, then the dBB approach, explored notably by Ward Struyve (see previous post), shows on a few toy models than one can give a precise meaning to space-time and its singularities in a non perturbative way (where the orthodox approach requires many layers of interpretation to understand an “emergent” space-time). This constatation may be only anecdotal, but it seems that collapse models provide an extremely intuitive way to couple quantum particles with a classical space time without really simplifying the situation if gravity is to be quantized as well. On the contrary, Bohmian mechanics seems to be unable to do a consistent semi-classical coupling but allows to easily construct toy models in which gravity is quantized. Foundations thus offer a guiding perspective to construct the future unification of the two long separated sectors of modern physics.

In more precise examples putting together gravity and quantum theory, theories with a clear primitive ontology have already allowed significant advances. The problem of fluctuations in inflationary cosmology [Sudarsky2009] has been much clarified by toy models of collapse (see again [Okon&Sudardky] and references therein) and theories inspired by dBB [Goldstein2015].

The research in foundations has also produced useful byproducts such as powerful numerical methods inspired by dBB [Struyve2015], notably used in quantum chemistry [Ginsperger2000] [Ginsperger2004]. The most important result discovered fortuitously thanks to foundations is no doubt Bell’s theorem. Indeed, John Bell, having realized that the impossibility theorems of Von Neumann and Gleason on hidden variables proved essentially nothing –as the very existence of Bohm’s 1952 theory showed– wondered if the non locality of the latter was inevitable. As this fact is often not known and often deemed surprising, let us cite Bell in “On the Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics”, published in Rev. Mod. Phys. in 1966 and which was written before the discovery of his inequality:

“Bohm of course was very well aware of the [non locality problems] of his scheme, and has given them much attention. However, it must be stressed that, to the present writer’s knowledge, there is no proof that any hidden variable account of quantum mechanics must have this extraordinary character. It would therefore be interesting, perhaps, to pursue some further ‘impossibility proofs’, replacing the arbitrary axioms objected to above by some condition of locality, or of separability of distant systems.”

A last paragraph which can be read as a program…

Reasoning in terms of primitive ontology may also be a way to bypass the difficulties of the reasoning in term of state vectors or operator algebras. Having a clear primitive ontology (in this case, flashes) is what allowed Tumulka to construct in 2006 a fully Lorentz invariant collapse model (without interactions) where such a result would have been hopeless at the wave function level. The resulting theory has no simple expression in terms of operator algebras but reproduces the predictions of quantum theory (up to  ). Bypassing the state vector may also give ideas to overcome the difficulties in defining rigorous quantum field theories with interactions [note: this is what later motivated this work]. Indeed, one may very well understand that a law (e.g. the value of a two point function) can be obtained through an iterative procedure, as a limit of something via the renormalization group. But it is the fact that the objects themselves can only be seen as limits that poses important mathematical problems. One may imagine that we some day have a well defined theory with a clear primitive ontology that only requires renormalization arguments to compute the dynamical law of the ontology, but not to define it. Instead of thinking the algebraic structure of quantum theory as primitive, as it is usually the case in axiomatic approaches to QFT, one may hope to obtain it as something emergent, from the dynamics of a primitive ontology (thus possibly bypassing some impossibility theorems). This is of course extremely speculative, but our purpose is just to argue that foundations may also have an interest in mathematical physics.

). Bypassing the state vector may also give ideas to overcome the difficulties in defining rigorous quantum field theories with interactions [note: this is what later motivated this work]. Indeed, one may very well understand that a law (e.g. the value of a two point function) can be obtained through an iterative procedure, as a limit of something via the renormalization group. But it is the fact that the objects themselves can only be seen as limits that poses important mathematical problems. One may imagine that we some day have a well defined theory with a clear primitive ontology that only requires renormalization arguments to compute the dynamical law of the ontology, but not to define it. Instead of thinking the algebraic structure of quantum theory as primitive, as it is usually the case in axiomatic approaches to QFT, one may hope to obtain it as something emergent, from the dynamics of a primitive ontology (thus possibly bypassing some impossibility theorems). This is of course extremely speculative, but our purpose is just to argue that foundations may also have an interest in mathematical physics.

Finally, a major interest of the clarification of quantum foundations is to liquidate an important number of prejudices that encumber modern physics, philosophy, and sometimes even the public sphere. One may very well hate dBB theory and prefer the orthodox formalism (that may even be preferable if one wants to do computations). However, the very existence of dBB, a theory that is compatible with all the predictions of quantum mechanics, makes many commonly held view about the purported epistemic implications of the quantum paradoxes manifestly inaccurate. Quantum mechanics does not imply that Nature needs to be fundamentally random, it does not imply that the observer is necessarily inseparable from the observed system, it does not imply a role of consciousness in any physical process, it does not forbid in principle the use of trajectories nor does it makes the simultaneous definition of position and velocity impossible (it forbids to observe them); it does not finally imply the existence of multiple universes. In the end, quantum theory demands almost none of the epistemic revolutions it is assumed to require. The only provable implication of quantum mechanics (experimentally verified) is the need for some form of non locality, but it is rarely this feature (absolutely unsurprising for the public) that is put forward. Physicists, without bad intentions, usually like to emphasize the mystery. A positive effect is to cover the field with a glamorous glaze and, perhaps, to improve its funding and attractivity. However, this does not go without risk and such a behavior blurs the line between science and pseudo science. The proliferation of New Age literature lending absurd virtues to quantum mechanics would seem like a laughing matter. The disturbing fact is that what one can read in those books is not so different, at least from the point of view of the public, from the things serious physicists may say during popular conferences.

Quantum mechanics is too important to neglect its foundations. A few simple results strongly clarify the status and implications of the standard formalism. Knowing them can help one feel better with the theory (which is not negligible for students) and also help get new ideas to extend it or prove new mathematical results. Having many viewpoints on the formalism also helps liquidate the misconceptions that physicists have unfortunately exported to philosophy and sometimes carelessly communicated to the public. Finally, there is no good reason to leave foundations to the exclusive attention of retired theorists…

(where

is the mass density operator) as a candidate for the mass density gives a gravitational field depending quadratically on the wave function. So in the end, the Schrödinger equation contains linear but also cubic terms in the wave function. And with that, all hell breaks loose and the quantum mechanical toolbox no longer works.

I have discovered the books of Ruwen Ogien too late, only roughly four years ago, with De l’influence des croissants chauds sur la bonté humaine (“Human Goodness and the Smell of Warm Croissants”), a profound yet entertaining book on experimental moral philosophy. Ogien made analytical philosophy cool. Philosophy is a game, you can ask questions, sometimes find answers, and even carry experiments. You need not let yourself smother by the bootstrapped bullshit of French theorists to attack hard questions: Ogien wrote in a sharp almost dry style, never hiding the weakness of an argument in convoluted prose. He popularized moral philosophy in the same way Dubner and Levitt popularized applied economics with Freakonomics. Extending the domain of ethics, he discussed pornography, love and ultimately illness. Ogien has greatly magnified my interest in moral philosophy and motivated my own

I have discovered the books of Ruwen Ogien too late, only roughly four years ago, with De l’influence des croissants chauds sur la bonté humaine (“Human Goodness and the Smell of Warm Croissants”), a profound yet entertaining book on experimental moral philosophy. Ogien made analytical philosophy cool. Philosophy is a game, you can ask questions, sometimes find answers, and even carry experiments. You need not let yourself smother by the bootstrapped bullshit of French theorists to attack hard questions: Ogien wrote in a sharp almost dry style, never hiding the weakness of an argument in convoluted prose. He popularized moral philosophy in the same way Dubner and Levitt popularized applied economics with Freakonomics. Extending the domain of ethics, he discussed pornography, love and ultimately illness. Ogien has greatly magnified my interest in moral philosophy and motivated my own